Every organization needs principles. Even the bad organizations, the ones that rob you blind, pick your pocket and leave you bleeding in the alley (think "insurance companies") have a set of guiding principles, however warped and twisted they may be.

I've always liked to think of my practice, the Center for Alternative Medicine, as one of the good companies. And for most of its existence, it has only had one stated principle. In organizational management language, its mission statement would go something like this:

Every organization needs principles. Even the bad organizations, the ones that rob you blind, pick your pocket and leave you bleeding in the alley (think "insurance companies") have a set of guiding principles, however warped and twisted they may be.

I've always liked to think of my practice, the Center for Alternative Medicine, as one of the good companies. And for most of its existence, it has only had one stated principle. In organizational management language, its mission statement would go something like this:

The mission of the Center for Alternative Medicine is to provide therapeutic interventions in a health-affirming environment to eliminate disease and dysfunction and enhance the well-being of the residents of Litchfield County and surrounding areas, without regard to race, age, sexual orientation, gender or financial status.

I've always preferred the short version: My job is to make people better using whatever means I have at hand. I'll take on all comers.

But the fact of the matter is, even the plain-language version embodies a number of underlying principles. And it wasn't until I was preparing a speech for the annual meeting of the Connecticut Society of Medical Assistants that, for the first time in 15 years, I sat down and actually elucidated them.

What came out of it was interesting. My 7 Core Principles, I've come to call them. And they truly are the principles that make this doctor, and his practice, tick.

This is latin, meaning "First, do no harm." It is my job as a doctor to, more than anything else, avoid injuring my patients. This principle is why I became the type of physician that I am. Although the mainstream medical community pays lip service to this principle, you could hardly call it a guiding element of medicine's philosophy. If it were, you would see a lot less blather about rising malpractice rates, and a lot more effort directed toward reducing malpractice. (Did you know that the number one cause of non-traumatic death in the U.S. is medicine? And that's according to published research.)

In contradistinction, my interventions for the same conditions are far safer and at least as effective, if not more so (fertility treatments, for example. Recent research has found a higher success rate for acupuncture than for the far more risky IVF.)

This simply means that I place my focus not on a single system, such as the cardiovascular system, or the pulmonary system, or the digestive system. Instead, I evaluate patients in terms of these systems' interdependence. Or, as the brilliant Buckminster Fuller in his dense eloquence has stated: "Synergy is the only word in our language that means behavior of whole systems unpredicted by the separately observed behaviors of any of the system's separate parts or any subassembly of the system's parts. There is nothing in the chemistry of a toenail that predicts the existence of a human being."

Understanding the whole by examining the interconnectivity of its parts -- the data network, if you will, that allows the brain, heart and stomach to coordinate their activities -- has led me to solutions for patients who have suffered for years and whose well-known specialists proved ineffective. In fact, it was precisely because they were specialists that they could not see the solution.

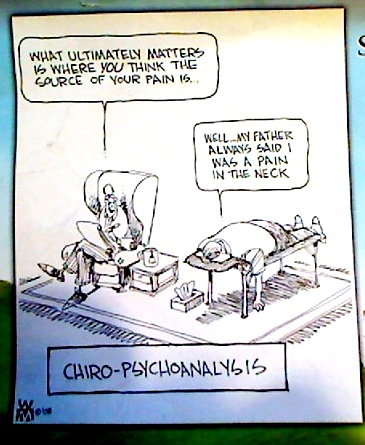

- Multi-disciplinary Therapeutics

Another way of saying this is that when the only tool you have is a hammer, everything looks like a nail. Any repairman worth his salt will equip himself with an array of tools, of the finest quality possible. A chiropractor who only adjusts has only a hammer; the medical doctor who only dispenses drugs posesses only a wrench.

I've got wrenches, hammers, pliers and a full set of torx drivers, by gum. And I'm not afraid to use 'em.

An accurate and finely-grained diagnosis is the key to success when you are doing alternative medicine. To properly treat my patients, I need to know more than that they simply have a case of sinusitis. I need to know why. I need to know what put that patient in a state that made them susceptible to this bug, and why they responded as they did. With that knowledge in hand, I can then go about fixing the underlying problem. To my mind, this is better than patching it over.

Ok, I did use some fancy words here, but I could find no others that could capsulate my intended meaning. I have found over the years that the greatest success comes when I work together with my patients to solve a problem. I work often as a mentor, a coach, a teacher. But I advise and recommmend -- never do I dictate. I work as a partner with my patient, and we each shoulder part of the burden.

This type of care cannot happen if a doctor is standing on a pedestal issuing commandments. The feedback and course modifications necessary to any successful outcome is missing in such a relationship.

Many of my patients come to me with problems they have dealt with for two, three, or five years. Rarely am I going to get a resolution in a week or a couple of visits -- though sometimes I have seen it happen. And for all my patients, I am looking not only how their health is now, but how it will be 20 years down the road. Because right now is the time to create the environment for future health.

Call me lazy if you want, but I prefer to figure out how I can provide the most benefit to my patients with the least intervention. This reduces the patient's costs, and it also refers directly back to principle #1. By minimizing my interventions, I also minimize any risk to the patient.

To me, therapeutic minimalism has a certain aesthetic appeal to it. Occam's Razor proclaims that the simplest answer in science is most often the correct one. And, the most minimal of equations, e=mc2, explains nearly an entire universe in four simple symbols.

So that's it. My Core Principles, if you will, the entirety of my practice philosophy. I found that developing and elucidating these core principles to be a valuable process, one that has given me insight into my professional past and a glimpse into its future. I recommend this process for anyone, especially to examine your personal life. You might discover some things about yourself that you thought you didn't know.

I'm kicking off this year's fall/winter lecture series with what I think may be one of my best -- and most important -- lectures ever. It will be held at 7 p.m. at the Litchfield Community Center, on September 22.

The title of the lecture is What To Do When The Drugs Don't Work, and will discuss the ways that alternative medicine can assist people suffering from chronic illness.

I'm kicking off this year's fall/winter lecture series with what I think may be one of my best -- and most important -- lectures ever. It will be held at 7 p.m. at the Litchfield Community Center, on September 22.

The title of the lecture is What To Do When The Drugs Don't Work, and will discuss the ways that alternative medicine can assist people suffering from chronic illness.