Nearly 17 years ago, my youngest daughter took her first steps at the airport on the way to attend my father's funeral. That moment, in the sterile hallway of an airway terminal, I experienced a strange crossing of emotions, as grief over the loss of the man who held my hand as I muddled my way through childhood collided into joy and pride as my daughter began her own long walk to independence. I didn't know what to do, really, so I did what my father had always done for me. I smiled at her and told her how very, very proud I was of her.

Nearly 17 years ago, my youngest daughter took her first steps at the airport on the way to attend my father's funeral. That moment, in the sterile hallway of an airway terminal, I experienced a strange crossing of emotions, as grief over the loss of the man who held my hand as I muddled my way through childhood collided into joy and pride as my daughter began her own long walk to independence. I didn't know what to do, really, so I did what my father had always done for me. I smiled at her and told her how very, very proud I was of her.

That's a memory I don't go to often, or willingly, but today it came unbidden and I suddenly realized how much of my life has revolved around walking, and the paths on which we walk. I was no more than 14 or 15 when, enlisted by my mother and my best friend, I helped to create a woodland trail. Back in the late 1960s and early '70s, when land was less precious and government less war-crazed and more civic-minded, the Corps of Engineers bought up a huge tract of land -- an entire watershed, as a matter of fact -- so that they could build a dam and flood thousands of acres of what had been perfectly arable land. The ostensible reason was as a flood control measure for the downstream Ohio River, but everyone knew that the real reason was to create an outdoor recreation area in what had been a relatively backwater part of the state. I'm pretty sure the governor's brother-in-law had a lot of real estate in the region, real estate whose value would see a sharp increase as soon as the dam was completed and the farmland flooded.

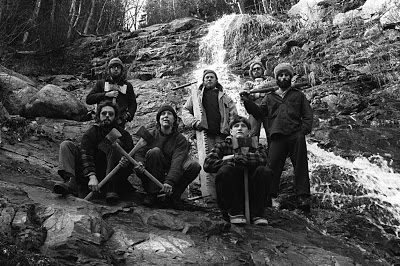

But that wouldn't happen for a few years, yet. So in the meantime, I, and my friend Brian, and my mother, and his family, all chopped and cut and sweated and trampled and created many miles of trail to be used by both hikers and equestrians.

My first backpacking trip occurred on that trail, also with my friend. Out of plans found in a Boy Scout Fieldbook, I had built myself a wooden frame, wrapped it in canvas, and hooked onto it a packbag purchased at a local Army-Navy surplus store. Brian and I walked, and talked, and tried to make a no-match fire and cooked some undescribable and barely edible mess of freeze-dried food. It didn't rain, which was good, because our tents, such as they were, were simple tubes of plastic held up by a length of parachute cord. But I so clearly remember walking along the side of the soon-to-be-dammed creek, and seeing the muskrat holes in the banks of the stream, and poplar trees holding themselves violently upright with roots gripped tightly around the sedimentary rocks exposed by the meandering stream.

We knew nothing about trailbuilding, of course, simply cutting through what seemed to be the most reasonable and scenic route along the creek and the alongside the woodlands that lined it. We all knew that it wouldn't last long. The Corps of Engineers' creep to completion was as sure as it was slow. That path -- my first path -- is long gone, a sunken treasure of my adolescence.

I thought nothing of it at the time, for in that headlong rush with which the young meet the future, I had already found another berth. The day after graduating high school, I left my home in Ohio for New Hampshire, where I had secured a coveted spot on the professional Trail Crew of the Appalachian Mountain Club. At that time, it was the only professional trail crew in the country, and had a hallowed 75-year history in the most blue-blood of conservation organizations east of the Mississippi.

As a graduation gift, my parents had bought me a private berth on the Lakeshore Limited, an Amtrak route from Cleveland to Boston. From there I would find my own way to Pinkham Notch, New Hampshire, the place to which my compass would always point for the next several years. My father gave me a kiss, and a hug, and told me that no matter what I did, as long as I did the best I could, he would always be proud of me. As my train pulled out of the station, I waved to my parents. My dad had tears running past the big smile on his face.

In the White Mountains of New Hampshire, I learned the craft of the trailbuilder. I learned how to drop a pine tree with a double-bit axe and skin the bark off it, sticky sap dripping from the naked wood, making it slippery to carry to its fate as a step or a footbridge or a waterbar. I learned how to quarry rock as large as bales of hay and roll its ungrateful mass to the trail, where I would dig a hole and expertly drop it in, leaving a flat, immutable surface to set foot on and another step in a long staircase up the side of one or another mountain. I remember one week counting in amazement after two of us, working together, had created 122 steps on a trail leading to Mizpah hut. Unlike the creek trail of my youth, these trails were made to last. Our goal was to create masterpieces that would last 100 years.

But building the Appalachian Trail was only part of my education. I also learned how to cook for six hungry men, how to motivate a ragged crew through their fifth straight day of rain and mud with a little snow mixed in for variation. I learned what it meant to be part of a tribe. I learned to love and be loved. I learned how to absorb the beauty and majestic power of the mountains and make it my own. The trail I was building was to my own manhood.

I emerged four years later, stronger, hardier, and with an unassailable sense of self. I knew who I was, and I knew the depths of my endurance.

Years passed, as they do, but the path never let me go. As I retooled from my first career to become a doctor, I also became a father. Thursdays, the traditional off day for chiropractors, became Daddy Day, and I soon found myself walking the wooded path holding the hand of Daughter #1, who contentedly ambled with me, stopping frequently to crouch down and intently examine a leaf. Or a bug. Or a pebble. Every week, we would walk along the same path, each trip filled with new discoveries.

One time we were walking along and she pointed to a log. "What's that, Daddy?" she said.

"That's a log, sweetie," I said.

"Where do logs come from?" she asked.

"A log is a tree that died and fell down," I told her.

Her eyes got wide. "It died? Why did it die?"

"Well, they have to make room for the other trees. See, when an old tree dies, it falls down to make room for a new, young tree to take it's place."

She chewed on that for a while. Then she took my hand and we began walking again. But she asked about it a few more times before she could really put her mind at ease about the whole subject.

Daughter #2 was the force behind my return to the mountains of my past. At the ripe age of 9, she decided she wanted to climb Mt. Washington with me. Of course, she thought the summit of Mt. Washington was a half-hour hike like the one to the summit of Mt. Tom here in Litchfield. She was a bit surprised on that June day when I pointed to that snow-capped summit half covered in clouds and told her that was where we were going.

No matter how you cut it, the trip up Washington is arduous. We went via Tuckerman Ravine, where we encountered our first snow, and then as soon as we hit the ridge, we entered the land of ice and clouds and wind. For hours we climbed, carefully moving from cairn to cairn so we wouldn't lose our way, as the path at that altitude was nothing but jumbled boulders and rock. By the time we reached the summit, visibility was down to about 30 feet, the wind was whipping us at 60 mph, and I don't even want to think about how cold it was. This was no simple hike for a nine-year-old. Daughter #2 was pushed hard by the trail, but she pushed right back.

After a short lunch break, we began picking our way down to Boot Spur. And as we reached the edge of the spur, a sudden gust of wind shredded the last of the clouds that had held us in blindness for so long.

"Look, honey, look!" I said, and pointed off the edge of the ravine. From 30 feet our visibility had gone to 30 miles, and you could see the whole majestic spread of the Presidential range and the valley from which we had climbed. My daughter's eyes grew as big as saucers. And I knew she would never look at the world the same again.

Today, I saw a new patient, someone who had been having back pain for several years, and the first thing I did, as I usually do with patients suffering from chronic back pain, was watch her walk. A biomechanically correct stride is important, and that's what I was analyzing, but as I did that, another part of my brain was thinking that how we walk says so much about who we are. And suddenly, I was taken back in time, to my daughter's first steps and my father's last. The friends who walked with me along parts of my path, and the miles I have walked alone. The bear I met in Maine, and the girl I met in Boston, who walks beside me still. And how even after all of these years, I can still skip surefootedly from root to rock and across the stream.

The skills of a trailbuilder are many. These days I no longer build anyone else's path but my own. But I'm putting the skills I learned walking the many paths of my life to good use, helping others walk along the paths they have created for themselves. There is little that could be more gratifying.