Inspired in equal parts by laziness, a fondness for offbeat experimentation, and personal growth, I have been walking to work for the past two months. It's not a very long commute by any standard, a pinch less than a mile, although the 8% road grade is relatively indisputable and I can't quite decide if it is in the wrong direction. As things stand now, I have a sprightly downhill jaunt in the mornings, and an uphill slog at the end of the day. And since it's so short, I've been walking home for lunch as well. Sometimes I insist that the directionality, or at least temporality, of the slope be changed, but at other times it seems perfectly fine. I suppose with regard to the kerfuffle that is local geography, the gods in fact do know their business, and I should leave well enough alone.

I started foot commuting by fiat one morning, when bike #1 had a flat tire and Bike #2 was on the repair stand for cable replacement. (Of course, I also have bikes #3 and #4, but we really needn't delve too deeply into my transportational quirkiness here). I have a difficult time justifying using an automobile for such a short distance, unless I'm coupling it with other errands. To me, such sloth smacks of an immorality commensurate with unfiltered Chesterfields, pool halls and Hudepohl beer. It also hasn't been that long since I finished reading The Old Ways, a book about walking the ancient paths of the U.K., which seeded my mind with the desire to see what a walker sees and experience the world from a walker's perspective. So I slapped on my office clothes and perambulated my way to work.

Inspired in equal parts by laziness, a fondness for offbeat experimentation, and personal growth, I have been walking to work for the past two months. It's not a very long commute by any standard, a pinch less than a mile, although the 8% road grade is relatively indisputable and I can't quite decide if it is in the wrong direction. As things stand now, I have a sprightly downhill jaunt in the mornings, and an uphill slog at the end of the day. And since it's so short, I've been walking home for lunch as well. Sometimes I insist that the directionality, or at least temporality, of the slope be changed, but at other times it seems perfectly fine. I suppose with regard to the kerfuffle that is local geography, the gods in fact do know their business, and I should leave well enough alone.

I started foot commuting by fiat one morning, when bike #1 had a flat tire and Bike #2 was on the repair stand for cable replacement. (Of course, I also have bikes #3 and #4, but we really needn't delve too deeply into my transportational quirkiness here). I have a difficult time justifying using an automobile for such a short distance, unless I'm coupling it with other errands. To me, such sloth smacks of an immorality commensurate with unfiltered Chesterfields, pool halls and Hudepohl beer. It also hasn't been that long since I finished reading The Old Ways, a book about walking the ancient paths of the U.K., which seeded my mind with the desire to see what a walker sees and experience the world from a walker's perspective. So I slapped on my office clothes and perambulated my way to work.

Let me note at the outset that I am not unfamiliar with walking, having been an avid hiker and backpacker for most of my life. However, I've never really integrated walking into my daily life to any great degree. So while the physical act was familiar and comfortable, the psychology of walking to places to which I once would only have cycled proved to be entirely novel.

--------------------------

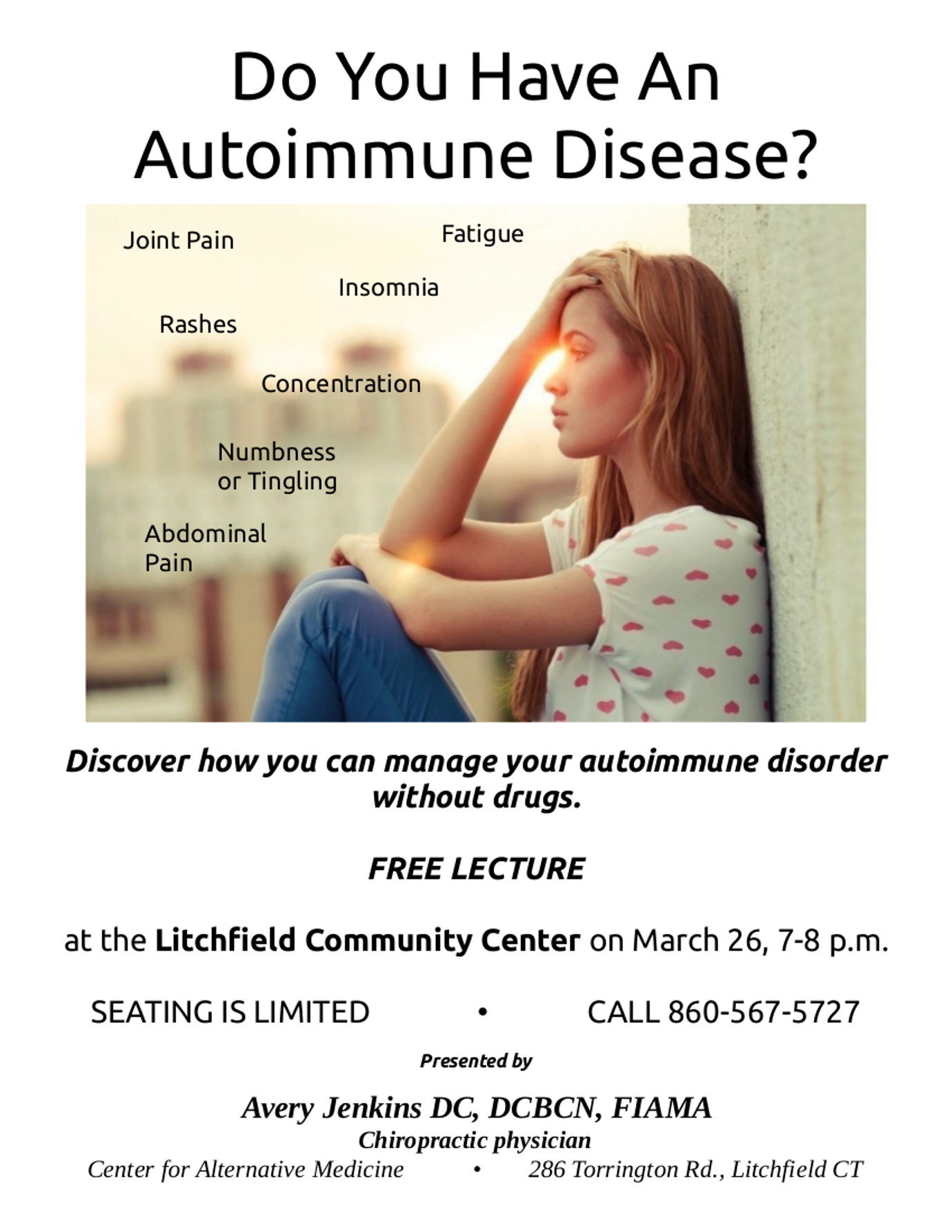

If you search the term "walking" on DuckDuckGo (that's a search engine like Google only without the massive invasion of privacy), the top ten results are dominated by walking as a health measure. Fitness walking, walking your stress away, walking your weight away, walking your heart to health...those are all well-accounted for and seem to be at the top of most pedestrian's minds. Less sought after is information on commuter walking, or utility walking. or walking #justforthehellofit. I suppose as a doctor focused on wellness and prevention, I should be happy about people's interest in being healthy. And it is true that programmed health measures are necessary to help people recover from chronic illness. However, these days, I am much more interested in the integration of exercise into our activities of daily living, as it makes the exercise more effective. I mean, when was the last time you saw someone stay on the treadmill for an extra 10 minutes just for the fun of it? But if you're walking home from work or the store, you might extend your walk that much just to enjoy a beautiful sunset.

Which brings me to perhaps the best reason for putting walking into your life: It fundamentally changes the way you see your world. Call it the time dilation effect. When you walk on a daily basis, your entire perception of time becomes altered. This is very strange, and could be very uncomfortable, for people brought up in car culture. When you go places by foot, you have to account for the time it takes to get there, something we rarely factor in when we travel by car. "Oh, it's only a 10-minute trip," we say. Two or three 10-minute trips later, and all of a sudden a half-hour is gone and you're rushing to pick the kid up from baseball practice on time and you *still* haven't finished all of your planned chores.

Walking forces you to reformat that process. You are impelled to add travel time to your calculations, as it no longer appears negligible. It isn't negligible. It's now 20 minutes to here, 35 to there. So you plan ahead, leave enough time to get there. And then the magic happens. All of a sudden, you're not in a rush. You check your watch once during the trip, yeah, you'll get there on time. The rest of the time, you are focusing on the journey itself -- the heat, the cold, the sun, the wind, the temperature. Instead of being literally bound and locked into a tiny, plastic, unchanging room with windows, you are engulfed by the endlessly changing panorama that is our world. Rather than rushing through your environment far faster than your senses can process it, you are savouring your surroundings. You are shockingly in touch with your environment in a very intimate, comfortable way, especially on routes you frequently walk. I've identified two medicinal herbs growing in the wild on my way to work that I'm going to harvest for making remedies. In a car, or on a bike, I never would have even known they are there. And the smells -- oh, my, does anybody remember what a summer night smells like? Not just when you're on vacation, but every night. And how the smells of the day and evening change throughout the year as plants bloom and die, and streams rise and fall.

The richness of sensory stimulation that occurs when you're walking makes the average automobile seem like a deprivation tank by comparison. Actually, let's be clear about it: An automobile is a roving sensory deprivation device. No wonder we are so eager to fill our cars with technological auditory and visual stimulants. Every time we get into an automobile, we are starving your senses, and we are replacing the sights, sounds and scents of our richer natural environment with the equivalent of sensory junk food.

Speaking of sound, what most pedestrians and cyclists also learn is that automobiles are extraordinarily loud. Road traffic is regularly measured at 80 dB; hearing damage commences at 90 dB. The intermittent traffic along my pedestrian commute highlights the extreme noise of the average automobile. Within seconds, birdsong and peepers are snuffed out by the roar of a passing car, or three. When you are subjected to those extremes frequently, you begin to realize also how damaging it is, not just physiologically, but psychologically, and it is reflected in our culture.

Even within an automobile, the noise level is typically around 70 dB. And what is the logical result of isolating ourselves from our environment and then filling it to the brim with artificial sights and sounds? If you can't hear your environment speaking to you, then it becomes unimportant. We have replaced the dialogue between ourselves and the world around us with a constant monologue in the echo chamber of humanity. All other voices have been drowned out to the point where most of us do not know how to listen to them even if we could hear them.

No wonder Mother Nature is screaming. We are unable to hear anything less.

So as we hear and see better when we are walking, so are we able to express ourselves more richly. Road rage is, in part, a result of being effectively gagged when we are in our automobiles. We communicate with others only through our brake lights, turn signals, headlights and horns. These are poor tools, effective only at communicating the coarsest of concepts. We can express only our direction of travel and various levels of concern, from a warning (a short beep-beep) to full-on anger (HONK!). Hand gestures, even friendly ones, are often lost to window glare, and you can forget about eye contact. Even if you are able to achieve it, the significance is almost null. Every cyclist and pedestrian can relate more than one incident of making eye contact with a driver before crossing an intersection, then having the driver almost plow into them because they had no idea that the other person was there. Inside a car, eye contact is as meaningless as a friend's description of a blind date.

Communications on foot is a different story entirely, and this was perhaps the first thing that I noticed as I began my bipedal commute. In a hurry, I thrust my body forward and step purposefully; when at ease, when enjoying my trip, I saunter. Between those extremes are shades of mood and attitude. I swagger, I hesitate, I plod through weariness and I walk with pride and strength, each step resounding through the earth. My gate changes with my mood, and with my entire body I can communicate my emotions to the world about me. And, yes, I have even danced from time to time. I had forgotten just how expressive the simple act of walking can be, and it is a joyful relief to be able to communicate so richly and so honestly with the world. Even on a bicycle, my thoughts could not be expressed so clearly as they can when on my feet.

Sometimes I think we have a world turned upside down on its head, where safety is in a speeding machine that kills 30,000 people per year, and danger is being on your own two feet.

It is truly a shame that walking should be such a forgotten activity. To the world at large, walking any distance for purpose rather than pleasure, has been delegated to the realm of the poor and the chastised. Why would anyone walk instead of drive, unless they couldn't afford a car or had their license confiscated for driving once too often after one too many? I'm sure that has been the assumption of more than one person who has driven by me over the past couple of months. I have even been stopped by the police, on the presumption that someone on foot must be engaged in some nefarious activity -- or at least have a couple of priors.

It was late, and dark, and I was slogging my way home. I saw the squad car pass and suddenly whip around in front of me, spotlight full on and blinding me. I heard a car door open and shut. A silhouette approached me.

"Good evening," the officer said. "Where are you going?"

"Home," I said.

"Where's that?"

"The top of the hill," I said.

He blinked.

"Where are you coming from?"

"Work," I said.

"Where's that?"

"Bottom of the hill," I said.

He looked at me. I looked at him. I smiled. He didn't.

"You have some ID?" he asked. I handed him my driver's license.

After fruitlessly checking my record on the computer, he returned from the cruiser and returned my license.

"Be careful," he said.

"I'll be ok," I said. "Just going to the top of the hill."

He shook his head and left.

As encounters with police tend to go, this wasn't unpleasant. But it did shake me loose from my personal point of view and realize how odd, and perhaps how dangerous, what I have been doing on a daily basis must seem.

I truly wish it wasn't that way. Sometimes I think we have a world turned upside down on its head, where safety is in a speeding machine that kills 30,000 people per year, and danger is being on your own two feet. Where comfort is defined by your insulation from your environment rather than your enjoyment of it, where noise is silence and the faster you go the more you have to rush.

Walking has its health benefits, and perhaps as a doctor, I should have written about that. How frequent walks strengthen your heart, clear your arteries, improve your digestion. All true. But the more important benefits of walking cannot be measured by cholesterol values or blood pressure. Walking is exercise for your body, but rest for your psyche. It brings you in touch with the Earth and lets your mind soar with the birds. Being bipedal is one of the most complex tasks we undertake as human beings, and when we cease to walk, we begin to lose our humanity.

Wisp of a Thing: A Novel of the Tufa by Alex Bledsoe

My rating: 5 of 5 stars

Wisp of a Thing: A Novel of the Tufa by Alex Bledsoe

My rating: 5 of 5 stars